More Stories from Our Community

Read more stories about communities coming together during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sharing Critical Information

©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Charina Pitzel

“Accessibility is not just a checklist. It’s a philosophy.”

Elizabeth Ralston (she/her), Independent Accessibility Consultant

I’m always thinking about things from a health and equity perspective. My work is at the intersection of community health, nonprofits, and accessibility. As a consultant, I primarily help organizations with capacity building by helping them engage more people in an accessible way. I’m also the founder of the Seattle Cultural Accessibility Consortium, which helps arts organizations improve accessibility for people of all abilities.

The term “accessibility” means being able to easily use something. It could mean being able to physically enter a place or it could mean access to knowledge. The need for this work is critical because, if there are barriers to access, then a person won’t have equal opportunities as everybody else.

I have lived experience with hearing loss and I have two cochlear implants to help me hear. So, while I don’t understand all disabilities, I have developed a good understanding of what people with different circumstances may need in order to access information.

Emergency access

When the pandemic started, I thought, “How can I help disability communities access information about COVID?” I reached out to the King County Department of Public Health, where I used to work, and encouraged them to make their communications more accessible.

For people with low- to no vision or hearing, we created videos. I filmed a video with a colleague who signs, where we talked about our different strategies in coping with being unable to read lips while people are wearing masks. We used captions and audio description in the video. We also created videos and messaging for neurodivergent people and people with cognitive disabilities, because there are a variety of ways that people can interpret information, depending on how their brains work. For people in the deafblind community who communicate with tactile interpreters (the deafblind person feels the interpreter signing into their hands), it’s been especially challenging as tactile interpretation is very difficult to do when you’re six feet apart. To address this challenge, we developed pamphlets in large print and in braille.

Vaccination was an important part of this communication effort. One of our working groups launched a special vaccine clinic for people with disabilities. We used targeted campaigns to communicate that vaccines were available in the first place, because people with hearing loss won’t be able to just overhear that information on the radio. We helped people access information about where to get vaccinated, but we also organized transportation, as that can be a big barrier for people with physical disabilities or who are blind or have low vision.

It was also important to educate the staff at the clinic about making various considerations for a variety of disabilities – not only people with sensory issues, but also invisible disabilities that can include mental health issues, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, autism, or anyone who is neurodivergent.

Making universal access the starting point

The pandemic unearthed a lot of inequities, particularly in BIPOC communities. It’s highlighted for me that intersectionality is a big issue because the more layers you pack on top of any single barrier, the harder it is for people to access anything – arts, education, healthcare. You have to consider the immigrant whose second language is English. How are they going to access this information?

As all of us age, we get more and more disabilities, whether they’re temporary or permanent. In the next 10 years, we’re going to get an explosion of an elderly community, and we have to think about how these people can access their own healthcare. It costs taxpayers more money if we don’t include people with disabilities in policy setting, in education, in healthcare, in any kind of planning.

Accessibility doesn’t have to cost that much, especially if you plan from the very beginning using a universal design perspective and build relationships with disability communities in the advocacy and hiring process. Accessibility is not just a checklist. It’s a philosophy that must be integrated within the organization. And if that’s not enough motivation, people with disabilities represent a billion-dollar industry. If we’re represented, we will show up.

Inclusion as a means to equitable access

What makes me hopeful is that people are starting to listen more and realize that they need to do better. The pandemic has helped make my work more accessible because it’s mostly virtual. Video calls are a perfect example of how easy it is for anybody to take a meeting or turn on captions. Theaters are more likely now to provide services like captioning upon request, so someone like me doesn’t have to plan their month around a single performance. I still have to call ahead, and my friend has to call ahead and make sure there’s wheelchair access, but someday I hope we can be spontaneous and just step off the street and buy a ticket to a show.

I think a lot of people are uncomfortable with the idea of accessibility because they don’t know how or where to start. They have preconceived notions about what people with disabilities want and need. So, the first step is to become really familiar with your audience. Include us in those conversations. As we do diversity, equity, and inclusion work, the accessibility piece needs to be part of that – so we’re working to dismantle ableism alongside dismantling racism.

To be any kind of ally, the best thing you can do is to be open, curious, and brave enough to lean into your discomfort. And when you hear or see something that doesn’t seem right with you, speak up.

– Told to Thanh Tan, independent journalist, January 2022

Website | elizabethralston.com

©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Alex Garland

“Whether it’s issues around mass incarceration, deportation, or houselessness, it impacts my friends and family.”

Oloth Insyxiengmay (he/him), Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Awareness Group (APICAG)

I’m an organizer. I do work around prisoner support, prisoner advocacy, prison abolition, and anti-deportation. I also work with a lot of collectives. Whether it’s Freedom Project WA, Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Awareness Group (APICAG), the Rooted ReEntry Collective, Free Them All WA, or others, the work is usually around the criminal legal system or carceral systems, where the folks who are disproportionately impacted are – unfortunately – Black, Indigenous, folks of color, and Southeast Asian folks.

It’s work I can’t escape, since family members, friends, and people in proximity with me are impacted by these systems every day. That’s the community I’m from.

Lockdown in Lockup

In the pandemic, a lot of us forget that there are incarcerated and detained communities, not just individuals but also families who are caged – and that they’re dealing with COVID-19 too. People who have never dealt with the carceral system don’t know it was already a struggle to get the departments of corrections to give appropriate treatment for any medical problem.

COVID has compounded that. There’s not a lot of space in these places, by design, so it’s nearly impossible to social distance. If there’s an outbreak, a lot of times they put sick folks into an even smaller area or throw them in the hole (solitary confinement), which effectively punishes them for having COVID. This comes on top of the concern that folks won’t get proper medical treatment if they get COVID.

We do a lot of work around advocating for medical treatment, advocating for someone’s release, or talking to policymakers. Our focus is on holding the DOC, policymakers in Olympia, and other people in power accountable for caring for our folks. We push for laws and policies that not only get people out, but also provide resources both before and after their release, so they not only survive but also thrive on the outside.

Building care, transforming justice

When Governor Inslee passed the initiative to release folks due to the pandemic, we started to build a community collective to support folks coming home. Many folks don’t realize that reentry work intersects with fighting houselessness. When folks come out, if they don’t have the support they need, they can fall into homelessness … and when they’re in poverty, they’re more likely to be reincarcerated.

People have the idea that criminal behavior is the responsibility or the fault of the incarcerated person, so they don’t think that person deserves help. But, in fact, systems of inequity and marginalization trap folks into situations that get them into the legal system in the first place … and once they’re stuck in that system, there are often no resources to get out.

Our work tries to help people see that it’s the responsibility of the system that caused that situation to help people get out of it.

My family was displaced from Southeast Asia due to U.S. aggression and U.S. policy in Southeast Asia. We came as refugees to a country we didn’t know and got placed in poor, under-resourced communities. When I was younger, I was excited about school, but I ended up falling into some of the stuff that comes with poverty. I was incarcerated at 15 years old, but I began to make connections with community members inside, like folks in APICAG. They provided the resources I needed: love and care and space to read, write, reflect, learn, and think about what it means to be someone like me in this society.

It’s not a coincidence that the faces I saw in my neighborhood were the same faces sitting across from me in prison. I can’t talk to a family member or a friend without that family member or friend being proximate to somebody who is being sentenced or currently detained or facing a judge.

Whether it’s mass incarceration, deportation, or houselessness, it happens because of racism and because of all the things that put the wealthy and privileged in one space and poor people of color into a marginalized space.

It’s a heavy feeling, and the pandemic just made it harder to navigate these systems. Usually, we navigate them together through relationships, but relationships have become more difficult during this time. I think it has a lot to do with unaddressed trauma that our communities disproportionately deal with, and therapy isn’t readily accessible for a lot of us. There’s no way to turn that off and “relax” or “reground” or “find ourselves” in this pandemic.

All we can do is organize, organize, organize.

Re-evaluating resources

Folks doing this work all resonate on the same sentiment: “We don’t have enough resources for all the folks out here that need support.” As one of the richest cities in the world, Seattle has resources, but what we’re doing about houselessness isn’t working. Continuing to do sweeps, moving folks around to different locations, trying to put them in housing without providing culturally responsive treatment … it doesn’t change anything.

When I think about my hopes coming out of this pandemic, I hope this is something we can address.

It’s hard to show up when we don’t have the resources to show up. There aren’t enough folks with the expertise and experience to do this hard community work in the first place … and when folks are able to show up to do this work, it burns them out. Non-profit jobs within Seattle pay on average $45-$65K for an annual salary, which isn’t a living wage here. But those folks are expected to show up and save the world. It can be counterintuitive for them – folks who are themselves directly impacted by racism and capitalism on an everyday basis are expected to change the system.

Maybe we can address these issues better by realizing that, if you’re thriving because you have a certain amount of resources, then the next person might need the same amount of resources to thrive as well.

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, September 2021

©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Alex Garland

“I hope people, especially people in power, are focused on the community.”

Sophia Brown (she/her) |

Graduate of Cleveland High

School

Fathima Garcia (she her) |

Graduate of Cleveland High

School

Sam Cristol (they/them) |

Educator at Cleveland High

School

Sophia Brown: It all started when [our teacher] Mx. Sam Cristol pitched the idea of having a vaccination clinic as a project for seniors [at Cleveland High School]. It was just an idea at that point, and we didn’t really know how it was going to happen.

Sam Cristol: The idea of a vaccination clinic was something I heard from two different educators in a staff meeting. It came from thinking about how we could make our school into a genuine resource center for the community. Because it’s a public school, it’s also a public building. It was just a question of who was going to run with this idea.

Fathima Garcia:

When Mx. Cristol brought this up, I

was super excited to be a part of

it.

Sam Cristol: I knew we had some

motivated students in the senior

class – like Fathima and Sophia –

who really care about service. They

were willing to run with it and make

it into a legacy that they’re

leaving behind.

Fathima Garcia: The culture of Cleveland High School is very community-driven. I have a passion for educating my community with the resources and tools that they aren’t fortunate enough to have. That’s what motivates me.

Sophia Brown: Especially during the lockdown [from COVID-19], there was a lot of time to get more in touch with my local community. I do running, so I spent a lot of that summer running around my neighborhood and getting to know it better. I got to really reflect on my place in Seattle.

Fathima Garcia: For all of us, COVID-19 was hard in different ways. I come from a very hardworking family. My parents both work two jobs, so it went from everyone being at school or at work to everyone being at home. At first, we didn’t really know what to do, but we made it work. We went on walks. It became a kind of family time we didn’t really have before.

Sam Cristol: I think the hardest thing was the way school shifted to being online. We did our best to build community and build relationships online, but it was hard. I know had a lot of amazing students pass through my class last year who I just don’t know very well. I felt fortunate I got some time in real-life to know students through the vaccine clinic project. We really wanted the clinic to be student-led, meaning students were working as non-medical staff. And they worked hard to make sure it became a culturally responsive clinic open to not just our students and families, but the South End community.

Sophia Brown: The South End of Seattle is a place that takes care of each other. The clinic was us taking care of ourselves. There was pride in being able to be the ones who was giving that gift to our own community.

Fathima Garcia: I think what drove us the most was to provide accessibility for our community.

Sophia Brown: We wanted to make sure that the people who need the vaccine could get to the vaccine. There wasn’t a bus line that went to the place where student workers got our vaccines, for instance. And a lot of our students and families use public transportation, so we wanted to make sure people could get here – and then feel safe when they were here. We also wanted to make it seem like it wasn’t a space where you had to get stabbed with a needle, but a place where you were doing your part to take care of the community. We wanted to make it a comfortable space. We even played music.

Sam Cristol: The student leadership did a great job of advocating for access. They made it clear: here are the reasons we set out to do this, here are our non-negotiables. Just one example, “we will have a clinic with translation services that aren’t just somebody on a phone.”

Fathima Garcia: As a Latina, a lot of my family members didn’t get vaccinated because of the language barrier. It’s that same problem when it comes to homeownership or going to banks, and I think they may be nervous because of things that have happened in their past. But there’s more trust if you’re approached by someone from your own community. When you see your own people doing something, then you will be more likely to do it too.

Sam Cristol: You guys also did a really great job of making those things a key part of the design of the clinic.

Sophia Brown: Even just the work [of building the clinic] felt like community. It was really interesting to watch people’s minds work on all the little things that you wouldn’t consider – because they know the community differently than you do. We had people who would mention certain languages we might want translators for. We had people who would bring up ideas for how to make accessibility better.

Sam Cristol: What that really makes me think of is how important relationships are to any type of social change.

Sophia Brown: It’s true. It’s the really tiny interactions with people that end up being a lot deeper than you think they would be.

Sam Cristol: We see it when a political candidate is running and they have all these lofty goals, but they don’t have any connection to the people that they’re going to represent. But you all set up this clinic, you staffed this clinic, then you interacted with folks at the clinic. There are relationships being built, and that’s a place to invest in and to continue to build.

Sophia Brown: It makes me think of a lesson we had in school about individualism versus collectivism. When you take an action, think about how it’s going to affect the others around you rather than just what the results of that action might do for you. I’m going to wear a mask not because I need to, but because it helps someone else. And it works the other way around too: give yourself the support you need. Reaching out, even if you feel very isolated, is always something you should try and do, especially during times like these.

Sam Cristol: Speaking personally, I’m just inspired to see how I can use the power and resources I am proximal to by being an educator to facilitate more students implementing the projects that they want to see and the leadership that they’re trying to do.

Fathima Garcia: A year from now, I hope people, especially people in power, are focused on the community. I hope we’re all focused not just on what you’re doing individually and what you might gain from what you do, but what we all could gain from it – together.

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, August 2021

Website | clevelandhs.seattleschools.org

©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Alex Garland

“People in power, people who have resources and are making the decisions, they have to step up and do something.”

Paula Houston (she/her) | Chief Equity Officer for UW Medicine in the Office of Healthcare Equity

In the Office of Healthcare Equity, our work before the pandemic was focused on making sure UW Medicine reaches the right people at the right time and in the right way, given that there are racist structures in place that disadvantage people of color and create health disparities – particularly for Black people.

Early on, it became clear to me and my team that COVID-19 would spotlight inequities in our healthcare system. One of our hospitals, Harborview, began collecting data on who was coming in for testing and what the positivity rates were by race, ethnicity, language, and housing status. Pretty quickly, we were able to see that our Black and Brown patients were experiencing stark disproportionality in infections and hospitalizations, specifically those who are Spanish-speaking and those who live in south Seattle, south King County.

Through COVID-19 response emergency funds, we opened our first testing site at Rainier Beach. Initially, people weren’t familiar with UW Medicine, but because I live in Rainier Beach and a colleague is also a south Seattle resident, we were able to leverage relationships built over the last 25 years. We met with 17 different community groups to explain why we were bringing COVID-19 testing to the community. We also saw some big disproportionality in Asian Pacific Islander communities, so we worked with the community health board that represents that community to set up some testing sites.

When it came time to shift our focus from testing to vaccines, we knew community education would be important. What we did not realize immediately was that we would need to begin that community education with our own workforce, particularly frontline workers with limited English proficiency. We wanted to ensure that they had the best information to make a decision right for themselves about getting the vaccine and, by extension, help their families and community also be accepting of getting the vaccine. So, we worked with clinician providers and interpreters who spoke 16 languages to create informational videos we called “Community Conversations- Straight Talk on Vaccines”. We encouraged staff to invite family and friends to participate and posted them on our YouTube site for anyone who wanted to use them.

Now, we do mobile vaccines and pop-up clinics all over King County, with a particular focus on South Seattle and South King County. This summer, we had a presence at the Juneteenth event held at Jimmy Hendrix Park in partnership with the Tubman Center for Health. They called it their Blaxinnation event. It was really informative to hear firsthand what some of the hesitation about vaccines is among the community. It helps to know how to give them all the information they need, instead of making them feel coerced. Our messaging is to say, “Vaccines are what’s going to help us get out of this pandemic. And until we are, you’ll want to protect yourself, your family, your friends, and your community.”

It’s intense, heavy work. Where I find my mental health therapy and where I get my emotional and spiritual reward, quite honestly, is in powerlifting. When I’m at the gym, I leave everything behind. When gyms closed due to the pandemic, many of us started makeshift workouts in our homes. A small group of us who are masters-level lifters and mostly over 50 were talking, and one teammate said, “What if we could borrow some weights from the gym and just set up our gym in my backyard?” And that’s what we did. At the time, everyone I saw was on Zoom, but I would see my gym community in-person to lift. It was time I really held sacred – and most of us hit several personal lifting records during the pandemic.

I continue to work in healthcare equity because I am beginning to see progress in reducing health disparities as we begin to dismantle white supremacist systems in our institutions that perpetuate inequities. We’re doing that by providing education and showing the data that has previously not been collected or collected and ignored. I want to be able to change the narrative about healthcare inequity and health disparities, to show that they are real. And I want to have the narrative backed up by evidence, to motivate people into action for change.

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, July 2021

Yubi © Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Chloe Collyer

“Young people are the now.”

Yubi Mamiya (she/her) | Junior at Shorewood High School, Director of Community Outreach at Washington State Legislative Youth Advisory Council, Founder of neXt Education App, and Youth Ambassador at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Discovery Center

This pandemic, as well as my work on the Washington State Legislative Youth Advisory Council (LYAC), has shown me just how powerful young people are. I’ve heard countless speakers and legislators say, “Young people are the future.” But I think that young people are the NOW. We can make change right now.

My whole goal as the Director of Community Outreach at LYAC is to advocate for youth-driven, change-making advocacy and civic engagement, because I want to give all young people equitable opportunities for the future. This starts young. It starts in our education system, just as it did for me.

In my role, I lobby for and testify on pieces of legislation that give young people, in particular marginalized students, a solid basis in real resources – whether that’s funding, technology devices, or inclusive curriculum – so as a society we’re able to deliver on an equitable education. With my nonprofit, the free neXt Education App, I focus on making learning opportunities accessible to marginalized students who may not have that now – by putting it online and making it personalized.

I hope that other young people will see and know that their voice is powerful, and that no one is going to hear it until they start sharing it.

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, February 2021

Website |

Next Education App

&

Washington State Legislative

Youth Advisory Council

Facebook |

@washingtonlyac

Instagram | @yubimamiya,

@washingtonlyac, and

@nexteducationapp

Essential Workers Meeting Everyday

Needs

©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Charina Pitzel

“We’ve survived pandemics before. We know how to survive.”

Shawn Thurman (he/him),

Registered Nurse, Seattle

Indian Health Board

I come from the Sac and Fox Nation

of Oklahoma, the Southern Cheyenne

Nation, the Shawnee Nation, and the

Caddo Nation – all in Oklahoma. As a

Plains Native living in the Pacific

Northwest, it’s a whole new

culture here that I’m learning

and experiencing.

For the past three years, I’ve worked as a nurse at the Seattle Indian Health Board, working specifically with the homeless Native community. People become homeless for a variety of reasons, but mostly their plans just didn’t work out and they fell on hard times. Any of us could end up in a similar situation – and when you’re there, it can be hard to navigate resources like health care.

The Seattle Indian Health Board is a federally qualified health center (FQHC) that is based in Seattle. We primarily serve the Native community, but we’ll serve anybody who walks through our doors for whatever they need – from housing to domestic violence support, to behavioral health, dental, and medical care. It’s pretty much a one-stop shop for anybody in the community.

I knew I wanted to work in the medical field after spending a lot of time in hospitals as a kid – many members of my family had health issues. So I started my collegiate career planning to become a doctor … but after volunteering in hospitals, I decided nursing is what I’m meant to do. I love every minute I’ve had in this job.

Here, we refer to people as “relatives” as opposed to “patients.” We want them to feel that connection to us as fellow Natives – so when they walk in, they feel like family and not just a number. Because of how vast our family ties stretch, Native people are not just centered on parents, siblings, grandparents, uncles, and aunts. Our way of seeing family stretches beyond those connections. Even for people outside the Native community, when they come in, they’re our relatives.

Good medicine in hard

times

When we first got reports of a new

virus, it was a mad scramble to read

up on research and track down daily

updates on how quickly COVID was

spreading and moving across the

world. This has been a

once-in-a-lifetime thing – something

we haven’t experienced since the

Spanish flu. And when you work in

health care, you know you’re

going to be on the front lines

whether you’re ready or not.

Through it all, the Seattle Indian Health Board has been innovative. We’re rising as a leader within federally qualified heath care. When our leadership, Esther Lucero and her team, requested personal protective equipment (PPE) and instead got a shipment of body bags, that was very symbolic of the federal government’s priorities. So leadership said, “We’re going to do this our way.”

That meant being flexible and intentionally listening to the people who had boots on the ground in the community. They realized we needed to bring relatives into our clinic to provide testing and vaccines and reach out to those without the means to travel to our clinic because of distance or money.

Our model uses traditional Indian medicine at its core. We have traditional medicine apprentices who come around twice a day to smudge the whole building. Our approach is also reflected in just talking to people as people – not necessarily about the vaccine, but just to get to know them. We use humor, which is almost universal in the Native community. Humor is always good medicine. When someone knows and trusts you, they’re more likely to come around. If they don’t, then you continue to love them and treat them as a member of the community.

Bringing that good medicine in everything we do has helped us build a model that translates to other FQHCs in other cities too. Through this model, we ended up securing more than enough PPE, we were the first organization within Washington State to get the Moderna vaccine, and our vaccination rates from the beginning far exceeded state levels. We made it our mission to continue to go to those people who didn’t take the vaccine on the first try. For some, it took two, three, four visits to convince them that the vaccine was safe. It’s a long game. You have to be patient.

Trauma-informed care

As the pandemic went on, it hit me

pretty hard. A lot of people have

left health care, and I understand

why you would. The burnout is real.

It wears on you to keep seeing

relatives coming in sick. But seeing

the relatives I know, those with

whom I’ve really connected,

that’s my driving force.

COVID magnified and amplified inequities in our communities. The homeless population got fewer resources than anyone, and there was a lot of fear coming from misinformation. That really motivated me to push for Native providers and for testing – and to reframe how to talk with people. You can’t say “stay home,” if you don’t have a home to go to. If it looks like we don’t understand something so basic, someone might think, “Oh, they’re not going to help me,” and fail to seek treatment or vaccination.

Equity issues and distrust aren’t new problems. They have lasted generations since the federal government first started interacting with Natives. A lot of historical trauma plays a huge part in how sick people are getting within our community. That history includes forced sterilizations and shipping people off from their homelands to big cities all across the country without resources. That trauma has carried through generations. Even our diet as Native people is not our original diet, and we now have a lot of diabetes and heart disease in the Native community. If you get COVID with those conditions, you’re already going to get hit a lot harder. It’s so complex, and there are so many factors that are contributing to how COVID is hitting the Native community.

When people look at Native culture, they often look at us as if we’re a relic of the past. When they step into our clinic, they’re like, “Oh my gosh, you guys are … still here.” We’ve survived pandemics before, and we’re going to push through this one too. We know how to survive. It can happen if we get back to traditional ways of taking care of each other.

Keep an open mind about the people around you. Think about the larger community among the people you interact with. It’s not just about “self.”

– Told to Thanh Tan, independent journalist, December 2021

Website | sihb.org

©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Charina Pitzel

“Early care and education is part of this country’s infrastructure.”

Lois Martin (she/her), Director, Community Day Center for Children

I was born and raised in Seattle’s Central District, where I own and operate the Community Day Center for Children. My mother, Lula Martin, founded the center in 1963 as a safe haven for single mothers. She and my father, Loy Martin, were foster parents and saw a community need for extra family assistance. Back then, the center had three or four children. Now, we have 40 children, ages 1 to 5, and 15 staff, including myself.

It wasn’t my plan to work in this field. From an early age, I was determined to become a “Black YUPPIE,” or “BUPPIE.” I studied computer science and accounting and worked for IBM. While on maternity leave, I began helping my mother with the center’s books. IBM offered a buyout to employees and I elected to leave, to work in the early care and education field. I now have a Master’s in Human Development and a Certificate in Early Care and Education Leadership from Harvard’s Graduate School of Education.

My introduction to the field began in the classroom as an aide. By the time my mother retired, I had enough experience to become the center director. I am intentional in my efforts to provide a wonderful early learning environment for children. When people use the term “daycare,” I gently correct them. Our teachers aren’t babysitters; they’re educated professionals with expertise in early care and education.

Essential but unsupported

In December 2019, when COVID was first discovered in Wuhan, I knew a pandemic would soon hit the West Coast. I reached out to the Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF), only to discover there was no plan in place to prepare for what would soon be a crisis.

After Seattle had the first U.S. fatality in late February 2020, our center closed for a month. As things opened up, those of us in early care and education were considered essential frontline workers. Some parents stayed home with their children to wait it out, but others didn’t have that option – and we needed to be there for them. So, in April, the center reopened with just seven children.

I didn’t know how we were going to make ends meet. We wanted to keep our staff working and paid. The majority of our staff are women of color, quite a few of us are over 50, and some have diabetes or high blood pressure. We opted to give our teachers hazard pay using small grants from various organizations. These monies helped us keep our doors open. Over the summer, parents slowly began to come back … but by September, our reserves were pretty much gone.

We were so utterly on our own. Even now, two years later, speaking about this is still extremely difficult and emotionally raw.

I had to design our protocols myself, based on CDC guidelines – there simply was no support at the beginning of the pandemic. Locating personal protective equipment (PPE) or supplies was challenging. But, with the center’s community of parents, teachers, and the early care and education community at large, we began to figure it out. We came together and supported each other. Parents or directors would message when PPE was found. “Costco has paper towels.” “Lowe’s has bleach.” We worked hard to assure a safe, healthy environment for our children – and we haven’t had one case of COVID in our center.

Our ability to survive comes down to how resilient early care and education teachers and directors can be. In the early care and education community, Susan Brown at Kids Company pulled together the Greater Seattle Child Care Business Coalition (GSCCSB). This group of center directors and owners have supported each other through this pandemic with shared protocols, exchange of resources, and doing whatever we needed to keep our doors open.

The payroll protection grant was a blessing. We wouldn’t be open now if it wasn’t for federal assistance during this ongoing pandemic. I am hopeful more funds will be forthcoming, directed to our industry.

Childcare as a public good

From the beginning, it was understood that public school teachers would teach from home – but that courtesy was never extended to early care and education. People view educators who work with little children differently.

In time, we will see how a lack of childcare will impact society. If you move children out of structured environments, it can influence their ability to meet educational milestones, even years later – this is especially true for marginalized families. How do we make up that lapse in time, and will we ever be able to? Women have left the workforce to take care of children. Some men have, but the majority are women. What advancements will be missed if brilliant working women have to stay home? What are we losing by not having this generation of workers? How will that impact our country’s innovation?

Early care and education is part of this country’s infrastructure. It’s a public good and a societal need. We need real investment – and third-party investments – to support families with small children. It must be an economic priority in the same way we invest in public schools, roads, bridges, or food supply chains. Parents should have the ability, regardless of income, to access the best learning environment for their child.

That is my takeaway from this pandemic. We can’t just invest in preschool and pre-K. We need to invest in the entire system, beginning at birth. Early care and education professionals support working families. We are a rock for parents. We open educational doors for future generations – and we can’t continue to work at poverty wages.

But this field instills in me a sense of hope. Children have, for the most part, been able to weather this so well. I am hopeful that – if this ever happens again – this generation will understand the sacrifices that have to be made for the good of the whole. It’s not just about your rights, but the rights of society – and children understand that better than many adults.

– Told to Thanh Tan, independent journalist, November 2021

Website | cdccinc.net

Ryan © Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Alex Garland

“My biggest fear and concern was bringing this virus back home to my family.”

Ryan Sheaffer (he/him) | Firefighter and EMT, Kirkland Fire Department

As a Firefighter and EMT for the Kirkland Fire Department, there are many things that we train for, but there was no blueprint for a pandemic. It was in these first few weeks that I felt the biggest impact of the pandemic. Two or three days in, we had to perform CPR on a COVID-19-positive patient at the Life Care Center of Kirkland, where the outbreak first occurred and where there were a lot of COVID-19 patients and several deaths.

Over the years, in my career as a firefighter, I’ve noticed that most people have a lot of respect and gratitude towards this profession. But last year, for the first time in my life during the pandemic, I felt somewhat ostracized for being a firefighter. There was fear, anxiety, and uncertainty. A lot of that was because of the unknown. We didn’t know how easily the virus was transmitted, or if the PPE was going to protect us. My biggest fear was not necessarily about contracting the virus myself, but about bringing it back home to my family.

We knew that signing up for this career meant dealing with any manner of first response. So, even though we hadn’t planned for this pandemic, responding to it was in our wheelhouse. Somebody needed to go out there and do the job – and to everyone’s credit, we did it.

It has been a really difficult time, but my family has always been there for me. I choose to look at this as a reset – a place to grow and learn from. The reality is that we need hope. Without hope, we don’t have much else. And I hope that this puts us in a better position as individuals and as a society when we come out of this on the other :side.

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, in March 2021

Website | Kirkland Fire Department

Kelvin © Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Alex Garland

“My job has been to safely transport my passengers to their destinations.”

Kelvin Kirkpatrick (he/him) | Bus Driver, King County Metro

As a King County Metro bus driver for 27 years, my job has been to safely transport my passengers to their destinations while monitoring situations inside and outside the coach.

Working so closely with the public, the word that comes to mind for what I experienced at the start of the pandemic is fear. I was immediately afraid for my son with autism who is susceptible to getting sick easily. Although the union stepped in to ease fears, without knowing much about COVID-19, I didn’t feel comfortable coming to work – and I couldn’t even take precautions, as masks were sold out. So, do I call in sick? Do I wait until we know more and can figure this out? Financially, I didn’t have the luxury to wait it out. I had to go into work and hope for the best.

What has stood out to me during this time is that the “public” – people who work as janitors or who work in fast food restaurants or grocery stores, people who may not have the luxury to work from home, and those who are doing everything to make ends meet and may not have enough to pay bus fare – they are very thankful we are operating. Every time an elderly passenger steps out, they go out of their way to wave or give us a thumbs up for our work. That makes me feel good.

I hope people take advantage of the vaccination process – and that we can get back on our feet and rebuild our economy. We’ve had to cut a lot of service and lay off more than a hundred drivers because we couldn’t run empty buses. I hope we can bring those drivers back because they have families and bills too. When the economy rebounds, job security is good for people like me. It’s the positive growth we need.

I hope we can work our way out over time … so we can look back at this and say, “We went through it, but we made it.”

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, in March 2021

Website | King County Metro

Richard © Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Alex Garland

“I feel a sense of duty that drives me to be here.”

Richard Chung (he/him) |Owner, Seward Park Market

As a Korean American born in Portland, Oregon, community has always been important to me. My father has been a community member his whole life, and I’ve always looked up to him. My father raised me by himself since I was 12. He has always been there for me and pushes me in a positive way. He started the Seward Park Market, building it from the ground up. With him aging, I took up his job. The work never stops, but it also gives purpose to be so deeply connected with the community.

I feel like the pandemic brought our communities closer together. When COVID-19 hit, stores like Safeway had limited hours. Since we’re one of the only independent stores nearby, we had a lot of people coming in for bare necessities, like toilet paper or masks. It was challenging to keep up with the supply and demand, but hopefully we provided everything they needed – or at least as much as we could.

As owner and operator, my job is making sure everyone gets the necessities and resources they need, seven days a week. I also like to check in and make sure our customers are in good health. Most of them feel like family since I’m here all the time, and they come in always to support our business. I feel a sense of duty that drives me to be here.

I feel blessed to be in a job where I get to interact with people all the time – even if it’s just asking how they’re doing or how their day has been. These kinds of interactions, especially in a tough time, are one way we can do something to help one another.

I do my best to make sure everyone gets along. It can sometimes get challenging. We had a fight turn into a physical altercation because someone didn’t want to socially distance inside our store. I only see this increasing with summer around the corner and more people venturing out. But even if they’re mean to me or trying to get violent, I calm the situation down. I don’t raise my voice and I find another solution.

I hope this pandemic ends soon … but until then, I hope everybody loves and checks in with each other and does as much as they can to help one another. That’s the only way I feel we can break out of COVID-19.

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, in April 2021

Facebook |

@jackschicken

Meeting the Needs of the

Community

©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Alex Garland

“Our liberation is tied. When you pour into community, community will pour into you.”

Cheryl Delostrinos (she/her), co-founder of Au Collective

We also realized there was a much larger need. We realized the communities we were connected to were on the far margins of being able to receive any type of government funding. The barriers to access were many: they spoke English as a second language, or they didn’t have a Social Security number, or they didn’t qualify as an artist, or they didn’t have access to a computer to fill out a form to get funding.

A big barrier to liberation is access to knowledge around how to connect – not just for the communities that I come from and directly work with, but also access for communities that have resources and wealth. At the time, I was hearing some people ask, “Where do I donate? How do I help?” So, our small team put our brains together on how we could move money from people who have resources to people who needed to be resourced. We already had a partnership with Benevity, and we also partnered with a LinkedIn influencer, Visa, Textio, and Microsoft as well. Altogether, we raised over $50,000.

Culturally, in a lot of our communities, it’s not an easy thing to ask for help. Many of us have trauma around money that leads to a scarcity mentality. Collectively, we need to understand the history of the wealth gap. We need to understand how wealth doesn’t necessarily look like finances, and how resources don’t necessarily look like money. Sometimes, resources look like time and energy pouring into one another through genuine connections and showing up – which happens when we understand we all have a role and we realize what our role is and how to fulfill it realistically.

All summer in 2021, I was intentional about working with community partners from different areas of Seattle, from different generations, and at different points in their career – and bringing them together under the shared value of centralizing community and decentralizing white supremacy. But we also took time to connect, to experience joy together, and to build together, support each other and share resources.

Something I heard through all of these conversations was the need for space to start building, to come together and connect, and to do it safely and in a place that felt welcoming, like home.

I am a resident of South Park, which was the neighborhood most impacted by COVID-19 – from the amount of people hospitalized due to COVID, to the loss of jobs and businesses. Here, the desire of community was to occupy more spaces along the Duwamish, to clean it up and preserve the natural habitat for animal and natural life and also for people who have been nurturing the South Park community. I was in community conversations around a plot of land right on the Duwamish River with a view of downtown Seattle. I was in the right place at the right time to learn that the landowner of that space wanted to give in some way and was willing to have it become a community space. It was an opportunity to piece everything together.

Centralizing community is the only way for our communities to survive and for us to build and live in the world that we all want to live in. We’re not trying to disrupt the system by being a part of it anymore. The pandemic has given us perspective and an opportunity to start identifying where areas of support are, what is needed. I think that people are ready to build. I think people have been ready to build. We all want the same thing – to see all our communities thrive.

I think COVID-19 has shown all of us that the structure and the system … yes, is effective in some ways, but it has also failed a lot of our communities in a lot of different ways. I’ve wanted to throw in the towel every week. But what keeps me going is the idea that when you pour into community, they will pour into you.

To see people wanting to connect, work together, come up with new ideas, it’s a reminder that what we are doing is bigger than us.

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, September 2021

Website | aucollectiveseattle.com

Dionna ©️ Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Alex Garland

“For tribal people, everybody’s related, everybody’s linked.”

Dionna Bennett (she/her), Program Director of Campbell Farm

I live in Wapato, located on the Yakama Indian reservation where I work as the program director at the Campbell Farm, a working farm and retreat center. I’ve been working here for the past 12 years in different capacities.

The farm has always been a safe haven. As a Wapato tribal member and African American, it’s a blessing to me and our community that the farm is a constant presence that has not gone away, that it continues to be a resource. It has brought food and love and care. The “give-back” is very real, and I’m passionate about it, especially for our kids and youth. I have a big passion about meeting our youth where they are and empowering them to do something great for themselves.

For tribal people, everybody’s related, everybody’s linked. We lost a lot of people from complications with COVID-19 – and from mental health issues. It’s forced me to really step up and look outside of the box to see how we can help people, how we get to people where they need us.

We’ve always served meals. Wapato is 96% at or below poverty. That’s a really huge number. At least half live in food deserts, which means that the nearest grocery store is at least 20 minutes away. Most rely on school food programs – but then the school shuts down because of the pandemic. So, we started serving meals and even just leaving meals on doorsteps. Because we follow a lot of the school district style, every component was met. Everyone got a protein, a fruit, vegetable and a starch. Within a month, no one ever received the same meal twice – and everything was prepared from scratch. It took a lot of time and a lot of love.

Soon, we decided to start serving the elders too. Because there’s such a need, we grew programming from serving children to serving this larger population. We were serving anywhere from 300 to 400 meals a day.

Our community work grew as the pandemic continued. Our society is already set up for failure for our people. It just made it that much more difficult to see and hear the judgments of outsiders being passed onto our reservation. There are all these judgements, and it makes me emotional to feel the weight of all these judgments.

In many places, domestic violence was on the rise with the lockdown and isolation. We realized that we have a lot of domestic violence, so we started to help moms who need safety plans and extra support in this pandemic – and going forward.

We also started the New Mothers’ Program to combat the high infant mortality rate that indigenous people face. We have only one hospital on the reservation, and it takes 30 or 40 minutes to get to that one hospital – so we partnered with the Pacific Northwest Medical Institute here. They offer clinical support via Zoom phone calls. We have some nurses through the Children’s Village clinic who can help answer questions. We also went out to churches and got diapers, wipes and formula donated.

When the homeless shelter closed down in Wapato, it meant that the nearest shelter was 60 miles away. There was no place for homeless people once they closed, so we started serving them too.

I figure, at some point, I will take a break from it all once things really slow down … but you don’t think about that when you’re in the midst of it. You just do it because it needs to be done. And when you’ve lived here for as long as I have, because this is a community I’ve been born and raised in, you can’t stop because you don’t want somebody to suffer.

I get hopeful watching things kind of slowly go back to normal. Watching kids graduate from high school, seeing new life – babies who were born during this pandemic time – that all gives me hope.

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, June 2021

Website |

thecampbellfarm.org

Facebook |

The-Campbell-Farm-166841460707

“Despite the struggles during this time, we’re still able to rally around each other and build up the causes we believe in.”

Kyle Melendez Daigre (he/him) | Student at ArtCenter College of Design, CA, and Exhibiting Artist & Volunteer at Onyx Fine Arts

I was in school at the ArtCenter College of Design in California last year when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. I’ve been home in Seattle since June 2020. With campus closing and everything shifting online, the collaborative process of art and artistic communities – normally an integral part of my classes – has been deeply impacted.

What was also concerning to me was that the future of Gallery Onyx, a local non-profit arts collective in Pacific Place Downtown dedicated to showcasing and celebrating artists of African descent in the Pacific Northwest, was also in peril.

I feel strongly about the importance and need for art in our communities, especially art from those that have been historically underrepresented or ignored. I’ve been a part of Onyx since I was 16. As an exhibiting artist and someone who helps prepare walls and set-up and take-down art and provides input on marketing, social media and visual aesthetics, I continued to volunteer even after I started college.

For most of 2020, there was a lot of uncertainty. Pacific Place was practically empty – and many volunteers no longer felt comfortable coming in. It was very difficult to go overnight from selling art constantly and having tons of visitors, to having nothing.

As stores opened up and foot traffic in the mall started to increase, new volunteers stepped up to help. Onyx has given me the opportunity to learn, grow and press forward on the career path I’ve chosen – and I wanted that same opportunity to be given to as many artists as possible. It’s essential to help build equity in the industry.

What I learned from this experience is the importance of a strong community. Artists who bring their work in, organizations that donate and give exposure to the gallery, and people who visit and volunteer – all of these are part of why it was possible for the collective behind Gallery Onyx to push through such a difficult time.

This pandemic has flipped everything upside down and shown how important community support is for both people and businesses rooted within those communities. It’s great that despite the struggles during this time, we are still able to rally around each other and build up the causes we believe in. This pandemic won’t last forever. It’s important to be resilient and keep supporting the people who make positive impacts on our communities to benefit both the present and the future.

Website | onyxarts.org

Facebook | @onyxfineartscollective

Instagram | @onyxfineartscollective

Kyle © Debi Gerstel

“The world is a better place when we’re not satisfied by mediocrity.”

Kyle Gerstel (he/him) | Student at Islander Middle School and Founder of KMG Center

I’m a 14-year-old musical theater geek who, when not doing schoolwork, lives and breathes theatre. However, the unfortunate but necessary halting of live theater demolished most of my life outside of school, much like Éponine’s love life in Les Misérables.

This inspired me to create theatrical opportunities for teens to stay safe, creative and connected during this moment of darkness. By creating opportunities to tell stories, I’ve been able to experience more theater and give back to the community that cultivated my love for it.

During the pandemic, I founded an experimental online improv troupe called Chimprov and I’m currently directing my middle school’s first musical in over a decade. I also wrote, directed and edited a 10-person online musical comedy called “Hamleton: A Quaranteen’d Musical.” Although I truly love Shakespeare’s stories, I wanted to make them more accessible by writing a piece that addresses the same themes while translating them to a modern setting.

The idea for Hamleton began in April 2020 when I was trying to find a new longform writing project as well as an excuse to see my friends (it was and is very difficult to get teenagers on a “social Zoom call.”) Rehearsals were held over Zoom, and the final performance can be found on YouTube.

For creators, performers and audience members alike, storytelling enriches our perspective of the world in addition to bringing us joy. My advice for others is that if you see something you want to change, find a creative way to change it. The world is a better place when we’re not satisfied by mediocrity.

“You are never too young to make a difference.”

Anika Consul (she/her) | Co-Founder of (You)th Cook, Student at Nikola Tesla STEM High School Class of ’21, Rising Freshman at University of Washington, and Youth Ambassador at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Discovery Center

I never imagined something like COVID-19 could happen. Initially, when schools closed, an extra-long spring break sounded like a dream come true for a high school junior. But by the end of March, no one knew what was going to happen.

Then I saw businesses close and a rise in unemployment and food insecurity. I knew I couldn’t just hope things would get better; I needed to actively work to make it happen. While baking virtually over FaceTime one day, my friends Anisha Karnik, Ananya Nandula and I came up with the idea of using cooking and baking for a cause.

That’s how our community service organization was born. Through You(th) Cook, we cook meals weekly and donate them to shelters in need across the Greater Seattle Area. We’ve provided over 3,500 nourishing, healthy and wholesome meals to The Sophia Way, Tent City, Helen’s Place, Congregations for the Homeless, the New Bethlehem Day Center and other homeless shelters across the Eastside of Seattle.

When it was announced that the 2020-21 school year was going fully online, we also reached out to elementary school teachers in the district and created a mini-baking curriculum to educate young learners about the science behind food through hands-on baking projects.

By starting You(th) Cook, I had the incredible opportunity to help others in need – and I learned how to mobilize my community during such an unprecedented time.

Its success only reinforced my belief that you are never too young to make a difference.

This work is important to me. I think of it like the domino effect – if you do something kind for one person, they’re likely to do the same for someone else. It creates a chain reaction of kindness. Seeing so many people reaching out through our initiative has been inspiring. It gives me hope that humanity has exceptional power to come together and conquer anything.

Website | (You)th Cook

Instagram | @you.thcook

Alyssa ©️ Jennifer Winter Photography

“The world put us online because they couldn’t handle us in person.”

Alyssa Jiwani (she/her) | Student at New York University Tisch School of Drama, Founder and Artistic Director of The Virtual Theatre Co, Overlake School, Redmond Class of ’20

I still cannot wrap my head around what happened in the last year. It feels like the world flipped upside down within weeks.

I was a graduating senior in the class of 2020 at the Overlake School in Redmond, Washington. The closing night of my senior musical was on March 8, 2020. It was my 19th and final show over the course of seven years. After that night, I never went back to Overlake again and I never got to hug friends or teachers again.

When the rest the school year was cancelled, I missed Overlake’s annual benefit concert, which I’ve led for the past few years. I decided to move it online to a huge, live-streamed concert benefitting Feeding America’s COVID-19 Relief Fund. I edited together performances from all of Overlake – 5th to 12th grade, faculty and alumni. We raised over $15,000 for COVID-19 relief. It was a heartwarming end to my time at Overlake.

Theatre and art got me through the trials and tribulations of high school, so when I heard from friends that their schools were canceling productions – and some schools were even defunding arts programs – I was horrified. I couldn’t imagine going through high school without that light.

Then I remembered how I put together the virtual benefit concert and realized that online theatre was a lot more plausible than people realized. I had a lightbulb then to create The Virtual Theatre Co (TVTC).

With its launch in July 2020, TVTC offers classes, productions and workshops. We have students from over 10 countries from around the world. Members of our creative team are working professionals in the theatre industry and theatre students from top-performing arts universities in the country. I run a workshop called Everything Broadway where we bring in Broadway stars, and students work with their inspirations. We’ve had Tony Award-nominee Taylor Louderman, TikTok star JJ Niemann, Wicked’s Jennifer DiNoia, Hayley Podschun, and DJ Plunkett, Mean Girls’ Mariah Rose Faith, Krystina Alabado, Kyle Selig, Cailen Fu, Frozen’s Caroline Bowman, Hannah Jewel Kohn and more.

One of our mottos is that the world put us online because they couldn’t handle us in person … and it’s true! Growing up, I was never represented on stage or on screen. I’m a young, short, tiny brown girl. I didn’t get opportunities handed to me, whatsoever – and I desperately want to change that for future generations.

Fighting inequity is the basis of TVTC, with its three main pillars to increase accessibility, inclusivity, and diversity. At TVTC, we are all trying to change the theatre industry for the better.

Theatre has the ability to be one of the biggest methods of change in our world. The younger generation of artists are coming in strong, and I’m excited about the future. Our generation is truly unstoppable.

Website |The Virtual Theatre Co

Instagram |

@thevirtualtheatreco

Ming-Ming © Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Alex Garland

“This was a community effort with one goal: To fight COVID-19.”

Ming-Ming Tung-Edelman (she/her) | Founder and Executive Director, Refugee Artisan Initiative

After 25 years of being a clinical pharmacist, I always wanted to give back to my community.

As an immigrant from Taiwan who came to the United States about 35years ago, I understand what it means to give a woman tools and skills to become self-sufficient and be financially Independent. My own grandma, a single mother raising three children as a seamstress inspired me that tools, plus skills can transform lives. Five years ago, I founded the Refugee Artisan Initiative (RAI). We employ refugee and immigrant women and train them in artisan skills and small-batch manufacturing so they can build better lives for themselves and their families.

The pandemic has been transformative for us. When COVID-19 first hit in March 2020, we were able to realize our strengths and pivot very quickly to provide what the community needed. Suddenly, sewing became a very valuable skill … to make masks, medical scrubs and face shields.

Since we are upcyclers with a lot of donated fabric – like, stacks of 100% cotton bedsheets, donated from California Design DEN – we had the best material to make masks to protect our community against COVID-19. I designed them in a day and put out our first GoFundMe campaign. Within two days, we raised over $10,000 then received a match of $10,000 from Rotary Club of Seattle NE. This enabled us to make more than 5,000 masks a week. A few husbands even helped! This was a community effort with the same goal: to fight COVID-19. We sent masks to postal workers – and across the country to New York and to the Navajo Nation which were hit hard by the pandemic. Partnering with Swedish Health System and their Community Health Investment we are making medical scrubs. All these opportunities allow us to hire more refugee and immigrant women coming to Seattle and using their sewing skills to make critical items while supporting for their families.

Living in a supportive community where people want to make a difference only motivates me more.

This year has shown human resiliency – and I hope it has also been a time of reflection. We can wear multi-layered masks and N-95s, but an actual vaccine can create immunity and stop the virus. That has given me a hope that we will come out at the end of the tunnel – and surprise ourselves by seeing that the sky is brighter and bluer.

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, in April 2021

Get Involved |

Refugee Artisan Initiative

Instagram | @refugeearts

Facebook |

@refugeearts

Fighting and Treating COVID-19

©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Charina Pitzel

“You cannot tell the story of disparities and inequities without telling stories of strength and resilience and power.”

Esther Lucero (she/her), President and CEO, Seattle Indian Health Board

Yá’át’ééh. I am Diné on my mom’s side and Latina on my dad’s side. Some folks are surprised when I tell them my first career was in the corporate world, where I achieved a lot of success, but I wasn’t giving back to my community. So I used that money and headed for med school, until I realized I was really interested in addressing issues grounded in systems. I soon fell in love with studying federal Indian law, so my graduate work was in public policy.

Now, I have the privilege of leading the Seattle Indian Health Board, a 51-year-old organization that operates as a Federally Qualified Health Center and Urban Indian Health Program, as designated by Title V of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act. We also have a public health arm – the Urban Indian Health Institute – that does research, epidemiology, evaluation, and data work. We’re uniquely positioned to provide direct-service healthcare, overall health and human services, residential treatment, and public health outreach. We’re part of the Indian Health Service system designed specifically for urban American Indians and Alaska Natives across the nation, but we serve all people, and we serve them in the Native way. We call our patients our relatives.

Meeting our own needs

At the beginning of the pandemic, I put in a request for personal protective equipment (PPE) from the Public Health department of King County. Instead of PPE, we received an anonymous box of body bags.

This may be shocking to people, but it’s not the first time that American Indian and Alaska Native communities have received this kind of response. Minnesota Representative Betty McCollum called to ask me about it, and I offered that maybe it was a mistake. She said, “It’s not a mistake. These things have happened intentionally.”

I think those body bags are a symbol that, to government systems, we’re not worth it – that we’re a cost, not a benefit. As American Indian and Alaska Native people, we have a unique relationship with the federal government, where the federal government owes us a tremendous amount of benefits and resources due to the secession of land. Depending on the administration, there have been attempts at eliminating that fiduciary obligation. It’s simply racist that people think of us in a way that doesn’t honor our strength, or the ways we come together to lead efforts, or our cultural ways of being and ways of knowing.

It has been a rare occurrence when we’ve been able to trust government systems, so instead we find trust within our own community.

Because we’re resilient, because we gather as a community to make sure that we are strong and move together, we pool our own resources. So, in relation to the pandemic, Louie Gong, who is part Nooksack and owner and CEO (at the time) of the lifestyle company Eighth Generation, donated $10,000 worth of PPE. Dr. Terry Maresca, one of our preceptors here at the clinic, rallied her medical students to bring in disposable and washable scrubs.

In the end, we wound up with more PPE than we could use and were privileged to donate it to other organizations that needed it.

Expanding the sphere of safety

As the pandemic continued, we had to change our whole service delivery model practically overnight. We went from 4,500 phone calls per month to 4,500 per day, so we expanded our data systems and staffed a call center. We moved in-person appointments to telehealth – and, for members of our community who don’t have access to cell phones, we created telehealth kiosks. To provide testing services, we acquired a machine to do onsite testing, which shortens the waiting time for results. We also amended our elders’ program so elders could continue to get a warm meal, visit with one another, get access to case management services – all without having to isolate from families and grandchildren.

We’ve had to come up with creative solutions to ensure that we’re there for our relatives who needed our services – and we did that while never closing our doors.

When vaccines became available, we couldn’t use the Pfizer vaccine because low temperature freezers were not available, so we decided on Moderna. We wound up being the first organization in the state to receive the Moderna vaccine, and I happened to be the first person in the state to receive the Moderna vaccine – it’s true! I wanted to show that I wouldn’t ask our community to do something that I wouldn’t do myself.

Due to the ingenuity and organizing skills of our staff, we were able to provide a thousand vaccines a day without wasting a single drop.

Through our public health arm, we worked with community- and youth-led panels to produce materials designed specifically to be understood by our communities. The 29 federally recognized tribes in the state of Washington allowed us to leverage their sovereign authority to implement testing and vaccination protocols, according to our community need. We started, much like the CDC recommended, with staff and elders. But we also expanded to our culture keepers, like our language speakers. We need to keep those folks and those epistemologies protected. 90% of all American Indians and Alaska Natives are vaccinated here in King County, which tells you how successful we have been.

We call our model “expanding our sphere of safety.” We prioritize the needs of the community, while at the same time building for a more far-reaching scope. We were so successful that the state of Washington even adopted our protocols, such as asking hospital systems to vaccinate staff from partner organizations. We also worked with community champions like Seattle councilmember Debora Juarez and Denise Juneau, then superintendent of public schools, to establish a collaboration with Seattle Public Schools to vaccinate special needs staff.

That’s what it looks like when the sphere of safety is empowered to expand.

Overcoming inequity

We face many barriers to equity – at the institutional and individual levels. Inequities are prominent in health outcomes and death rates. Our people have been hit hard. Folks experiencing homelessness or living in poverty may not be able to isolate or may not have access to PPE or hygiene products. Our undocumented relatives may be scared to seek services because they don’t know if becoming part of a national database could make them targets of ICE.

As a society, we already know how to overcome challenges of inequity. It takes two things: first, transferring resources and, secondly, transferring power.

There’s a lot to be angry about. At the same time, we’ve seen the largest investment in infrastructure than we will probably see in my lifetime. That offers a chance to escape that scarcity mentality and focus on economic opportunities. We have two additional clinics opening next year, and a dental mobile unit. Those things are massive!

But you cannot tell the story of disparities and inequities without telling stories of strength and resilience and power. At the Seattle Indian Health Board, we’ve learned what we’re capable of. We stand together in community – and we’re unstoppable.

We, as American Indian and Alaska Native communities, regardless of whether we live on our tribal lands, in our reservation systems, or in urban environments, are all tribal people, and we will always band together for the well-being of our communities. We are current and modern and innovative and smart and strong. Like our indigenous ways of being and knowing, many folks can learn from us and stop hoarding the resources. We’re still here. We’ll show you the way.

– Told to Thanh Tan, independent journalist, November 2021

Website | sihb.org

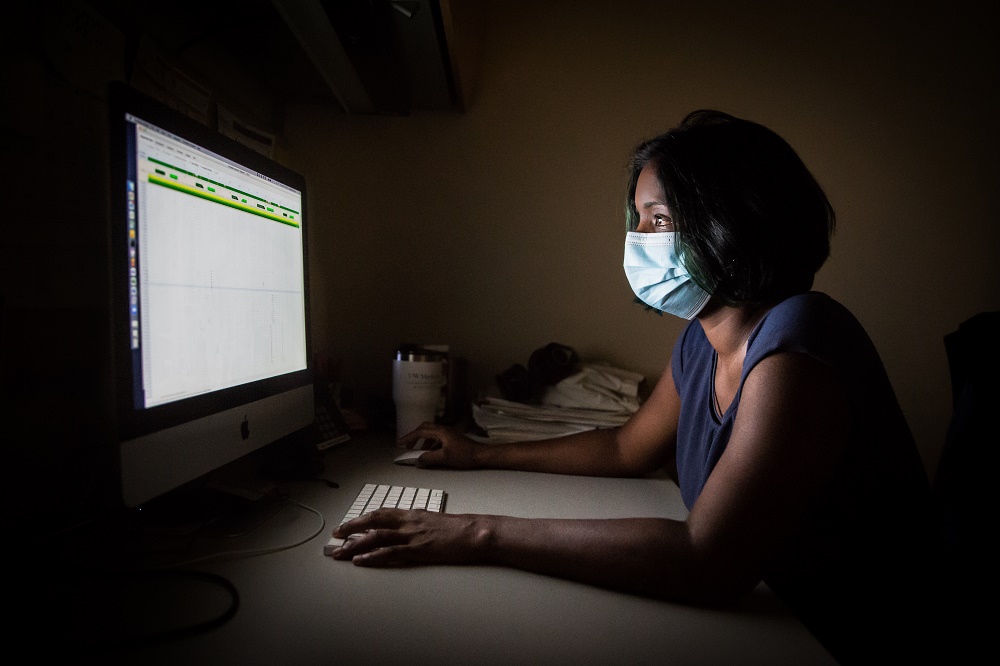

©Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Charina Pitzel

“We can’t deny we are globally connected.”

Pavitra Roychoudhury (she/her), Computational Biologist, University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

I’m a computational biologist at the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. My specialty is working with the genomes of viruses, which means analyzing the nucleic acids, that’s DNA or RNA, in a virus.

From the beginning of the pandemic, my colleagues recognized the need to sequence the virus. Before COVID-19, I was working with human herpes viruses, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), so I was able to apply those skills to SARS-CoV-2 – the virus that causes COVID-19.

February 28th was the day the first SARS-CoV-2 test sample arrived in our lab. We put it on our sequencer as fast as we could and by the next day we had analyzed our first genome – “UW1”–which was the third genome for Washington state.

When you get tested, you’re given a nasal swab which is then processed for your test result. If it’s positive, we take that sample and use lab techniques, mathematics and computing tools to determine the genetic sequence – or genome – of the virus in that sample. Initially, there was intense interest in using genetic sequencing to understand if cases were from travel or local transmission – and if local, how much community transmission has there been? But even back in March 2020, we knew we were behind in this pandemic. We knew the horse had left the barn – and bolted.

Then, for a large part of 2020, we thought this virus was behaving in a somewhat expected manner, but towards the end of the year, we saw variants come out of the UK and elsewhere that were spreading rapidly. We realized we were flying blind here in the US because of how few positive tests were sequenced. When you hear about variants, it’s the genetic sequence of virus samples that gives clues into what might be happening. Different mutations might impact disease severity or infectiousness, or they might indicate if the virus is escaping vaccines. The new variants really made us focus on sequencing, to scale-up our efforts.

People used to say things like, “Why aren’t we sequencing more and faster?,” but the reality is that in addition to a lack of funding and support, a lot of us have experienced burnout. Since the start of the pandemic, we’ve worked hard while taking only a little bit of time off. Because our lab is a testing lab, we are considered essential workers. For all essential workers, a huge amount of credit needs to be given to families and support networks. For me, that’s my husband and my daughter. My daughter is five and she really gets it. That it takes a village––at work, at home, and in the community – to come together to fight this pandemic.

Vaccines have shown that they are the greatest tool in tackling this pandemic. Without the genetic sequence of the virus, we would not have been able to design the vaccines we have right now. And yet there are huge inequities related to vaccine availability and distribution and uptake. As community members, we need to see what we can do to convince those who are unvaccinated to get vaccinated. Sometimes people are quick to point the finger at the unvaccinated and say, “Oh, these people are just choosing to be unvaccinated.” But not all unvaccinated people are driven by misinformation; for some, there are barriers, including structural issues. Can people take time off to recover the day after they receive their shot? Have we created safe spaces for people to do that, or to bring up any concerns they have? Because a lot of them are valid concerns and I think there are many things that we can do to address some of these inequities.

There’s still more to be done to make sure we turn the corner with COVID-19. People should recognize that, when we talk about travel restrictions and all the inconveniences related to the pandemic, there are populations that are still vulnerable to this disease – here and globally. Let’s not forget children all around the world are still not eligible for vaccination. Because we are connected, outbreaks in all those populations will ultimately impact us, so we need to think beyond our local communities. That’s going to make a difference over the next few months in this pandemic – and in future pandemics.

What gives me hope is science and the speed at which we have been able to tackle COVID-19. It’s the result of a lot of people coming together, often at great cost to themselves, and taking on incredible amounts of responsibility. For this pandemic and any other pandemic, what’s needed is for us to come together and take whatever skills we have and put them to good use.

– Told to Marcus Harrison Green, South Seattle Emerald, in April 2021

Website | dlmp.uw.edu/research/centers

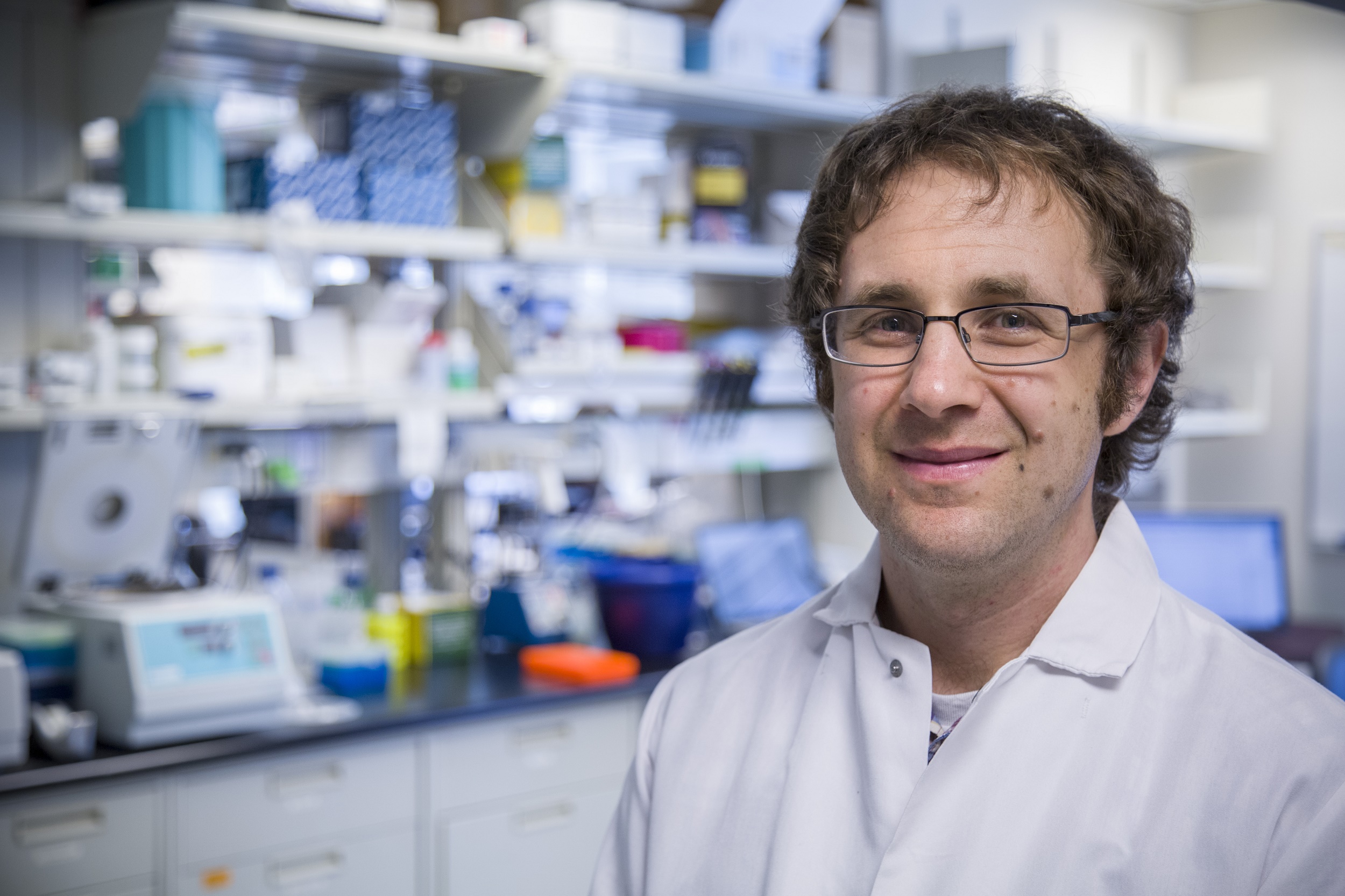

Jesse © Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation/Alex Garland

“When most people are vaccinated, this could be a lot less serious.”

Dr. Jesse Bloom (he/him) | Associate Professor, Fred Hutch Cancer Research Center, Affiliate Associate Professor, Genome Sciences & Microbiology, University of Washington, and Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute